Acid-Related Conditions: GERD and Peptic Ulcer Disease

What is GERD?

GERD is an uncomfortable, but unfortunately, very common condition. It’s often confused with acid reflux, but GERD is a more extreme form of this situation. Acid reflux refers to the occasional reflux of acid up from your stomach and back into your throat. This is bothersome, but not dangerous since it occurs rarely. The most common treatment for acid reflux is over-the-counter (OTC) antacids.

To learn about antacids read this blog on OTC drugs for acid reflux .

GERD, on the other hand, is a term used to describe reflux that happens more than twice per week for a significant amount of time. This then needs to be treated with lifestyle changes and often medication.

GERD can cause a lot of damage to your throat if left untreated. Your stomach has a thick mucus layer that protects the stomach from its own acidic contents. The throat does not have this, so when acid is refluxing up into the throat, this can actually cause a lot of damage to the throat tissue. Eventually, this can cause something called “erosive esophagitis”, a condition in which swallowing becomes uncomfortable due to the extent of damage.

How Can GERD be Treated?

Lifestyle Changes

There are many risk factors for developing GERD, some are avoidable by changing lifestyle habits.

- Diet: Fatty, acidic, and spicy foods, as well as caffeine and alcohol, can worsen reflux symptoms. Limiting or avoiding these can help reduce GERD flare-ups.

- Eating Habits: Large meals or eating late at night can trigger reflux. Try eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoid eating close to bedtime.

- Timing Before Bed: It’s not just eating late, but lying down soon after eating that increases reflux risk. Stay upright for at least 30 minutes to 3 hours after meals to let gravity help keep stomach acid down.

- Quit Smoking: Smoking damages your throat and weakens the muscle that keeps stomach contents from coming back up. Quitting smoking can reduce GERD risk and improve overall health.

- Weight Loss: Excess weight puts pressure on your stomach, increasing the chance of acid reflux. Losing weight and engaging in regular, moderate exercise can significantly reduce GERD symptoms.

Medication to Treat GERD

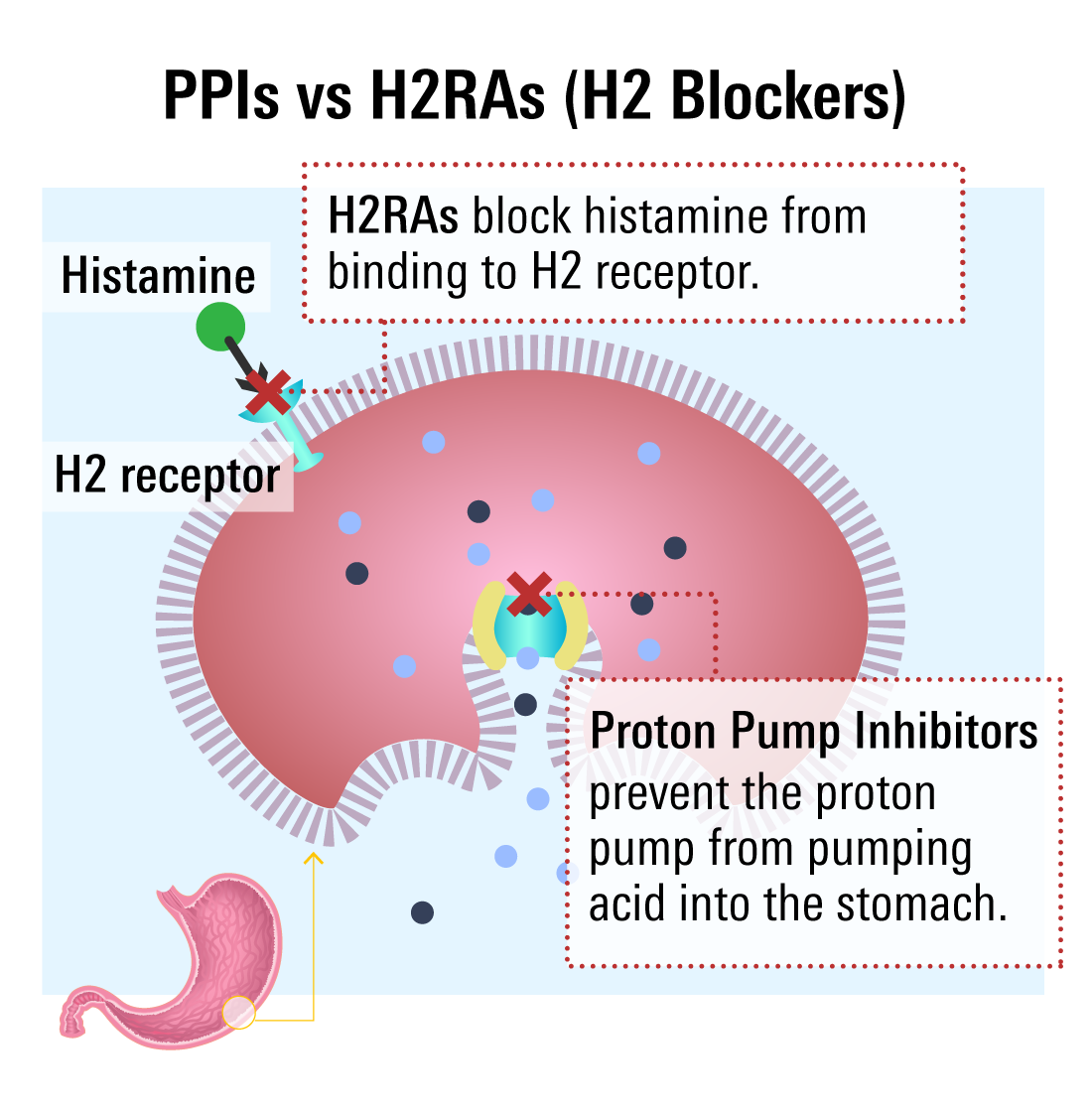

If lifestyle changes aren’t enough to control GERD symptoms, medication is often the next step. The two main types of medications used are:

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

- Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs)

Both are effective for short-term relief, but PPIs are generally preferred for long-term treatment. However, long-term PPI use may carry some risks.

Learn about the health risks when taking PPIs long-term

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs block the acid-producing pump in the stomach lining, reducing acid at the source. They take a few days to start working but offer long-lasting relief.

Common PPIs include:

PPIs are usually prescribed short-term for active GERD treatment, but this can be extended longer-term in order to treat erosive esophagitis or for longer-term maintenance therapy.

H2RAs to Treat GERD

H2RAs work earlier in the acid production process by blocking histamine receptors that signal the stomach to produce acid. They act quickly but may become less effective over time due to tolerance.

Common H2RAs include:

H2RAs generally have fewer side effects and fewer drug interactions than PPIs, but effectiveness can vary from person to person.

Important Considerations

Not everyone is a candidate for PPIs or H2RAs. Always share your full medical history and list of medications (including over-the-counter drugs) with your healthcare provider before starting treatment.

What is Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)?

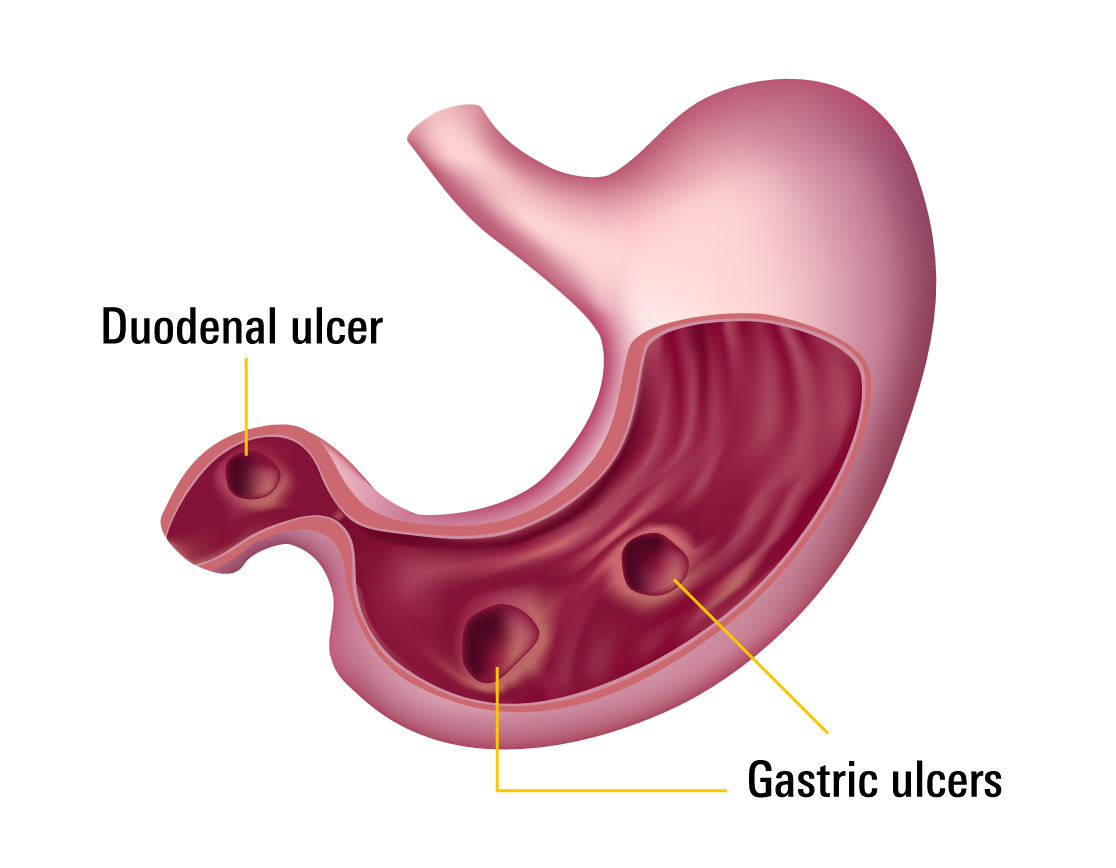

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to painful sores, or ulcers, that develop in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum (duodenal ulcer). These ulcers form when the protective lining of the digestive tract is damaged and the underlying tissue is exposed to stomach acid.

What Causes Ulcers?

Stomach acid is very strong, but the stomach and duodenum are usually protected by a thick mucus layer. When this mucus is worn down, acid can damage the tissue, leading to an ulcer. Because the area remains exposed to acid, ulcers can be slow to heal without treatment.

Contrary to popular belief, stress and spicy foods do not directly cause ulcers. The two main causes are:

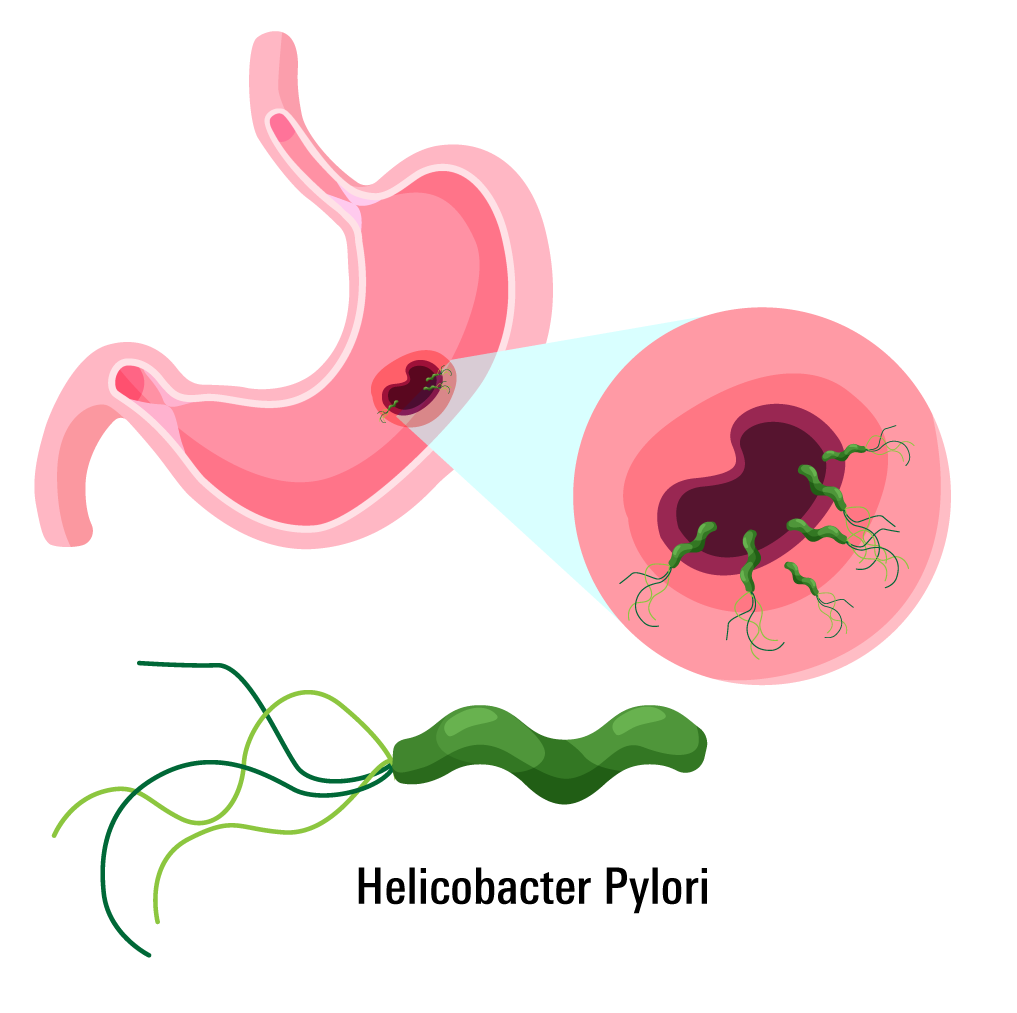

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection

- Long-term use of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)

H. pylori-related Ulcers

H. pylori is a bacteria that survives in the acidic stomach by neutralizing its surroundings and breaking down the protective mucus. When the mucus is compromised, acid damages the tissue, causing an ulcer. H. pylori ulcers are more common in the duodenum. These ulcers can be persistent and often require a combination of antibiotics and acid-reducing medications to treat.

NSAID-related Ulcers

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen and naproxen can irritate the stomach lining and reduce prostaglandins, chemicals that help maintain the protective mucus layer. This makes the stomach more vulnerable to acid, leading to ulcers. NSAID-related ulcers are more common in the stomach and can be more dangerous, as they are more likely to cause bleeding.

How to Treat Different Types of Ulcers

Preventing Ulcers Without Medication

While medication is often needed to treat ulcers, prevention is key, especially since having one ulcer increases your risk of developing more.

To reduce your risk of H. pylori ulcers:

- Use clean, reliable running water whenever possible.

- Be aware that living in crowded conditions or with someone who has H. pylori increases your risk, as the bacteria can spread through saliva and other body fluids.

- While these factors aren’t always within your control, understanding them can help identify and protect those at higher risk.

To reduce your risk of NSAID-related ulcers:

- Avoid long-term or high-dose NSAID use when possible.

- Use alternative pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, if appropriate (note: acetaminophen is not suitable for people with liver disease).

- If NSAIDs are necessary, your doctor may prescribe a low-dose PPI alongside to protect your stomach lining.

Medication Use in Treating Ulcers

Once an ulcer has developed, medication is the primary treatment. The approach depends on the underlying cause.

H. pylori-Related Ulcers

- Treated with a combination of 2–3 antibiotics (e.g., clarithromycin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, or tetracycline).

- A PPI (e.g., esomeprazole) is also prescribed to reduce stomach acid and promote healing.

- Treatment typically lasts 14 days to eliminate the bacteria and allow the ulcer to heal.

NSAID-Related Ulcers

- The first step is to stop NSAID use, at least temporarily.

- A PPI is then prescribed to reduce acid and allow healing.

- In some cases, an H2RA may be used instead of a PPI, depending on individual needs and tolerability

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection - Symptoms and causes. (https://www.mayoclinic.org.). Accessed 12 July 2022.

- Smoot, D. (1997). How Does Helicobacter pylori Cause Mucosal Damage? Direct Mechanisms. Gastroenterology, 113(6), S31-S34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)80008-x

- Drina, M. (2017). Peptic ulcer disease and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Australian Prescriber, 40(3), 91-93. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2017.037

- Wallace, J. (2000). How do NSAIDs cause ulcer disease?. Best Practice &Amp; Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 14(1), 147-159. doi: 10.1053/bega.1999.0065