All About Hemophilia

What is Hemophilia?

Hemophilia is a rare genetic disorder in which the blood does not clot normally. In typical situations, if you accidentally nick yourself while shaving, the bleeding tends to cease relatively quickly as your blood forms a clot to seal the wound. Over time, a scab forms, and the cut begins to heal.

However, individuals with hemophilia experience delays in the formation of this clot or may not form it at all. As a result, they are prone to prolonged bleeding, even from minor injuries, and may also experience internal bleeding without an apparent cause. This poses a significant risk, particularly in more severe injuries, as it can lead to significant blood loss.

Moreover, hemophilia carries the additional danger of spontaneous bleeding. This often manifests in joints and can occur seemingly at random, although sometimes it is linked to minor incidents like accidentally hitting your knee on a coffee table.

Different Types of Hemophilia

There are two main types of hemophilia: hemophilia A and hemophilia B.

Hemophilia A

Hemophilia A, also known as “classic hemophilia,” is the more common form of the condition, with roughly 1 in 5,500 births in the United States being male babies with hemophilia A. This form of hemophilia has a decrease in amount of a functional clotting factor called factor XIII (8 in roman numerals) also referred to as FXIII.

A reduction in the amount of functional FXIII results in decreased or even completely absent clotting following a bleed. The exact mutation leading to this condition can sometimes be characterized with genetic testing, but this is not commonly done as it is expensive and doesn’t change the treatment strategy.

Hemophilia B

Hemophilia B is the less common of the two conditions, resulting in roughly 1 in 19,000 male births in the United States.

Hemophilia B is sometimes referred to as "Christmas disease" due to its association with the surname of the first patient with the condition, Stephen Christmas. In 1952, Stephen Christmas, a young boy, was admitted to a hospital in England with a severe bleeding disorder. Researchers later identified his condition as a clotting factor deficiency, which was named hemophilia B or Christmas disease in his honor.

This condition is a result of a deficiency in the amount of functional clotting factor “IX” (9 in roman numerals). This is also essential for clotting to occur and a deficiency results in increased bleeding. The exact mutation can also be characterized for hemophilia B, however there are not as many well characterized mutations as with hemophilia A.

How Do You Get Hemophilia?

Hemophilia is caused by an absence of certain proteins called clotting factors and is more common in males than females. The ratio of male to female with hemophilia A is 1 female to 5,000-10,000 males, I female to 1,000–30,000 males with hemophilia B.

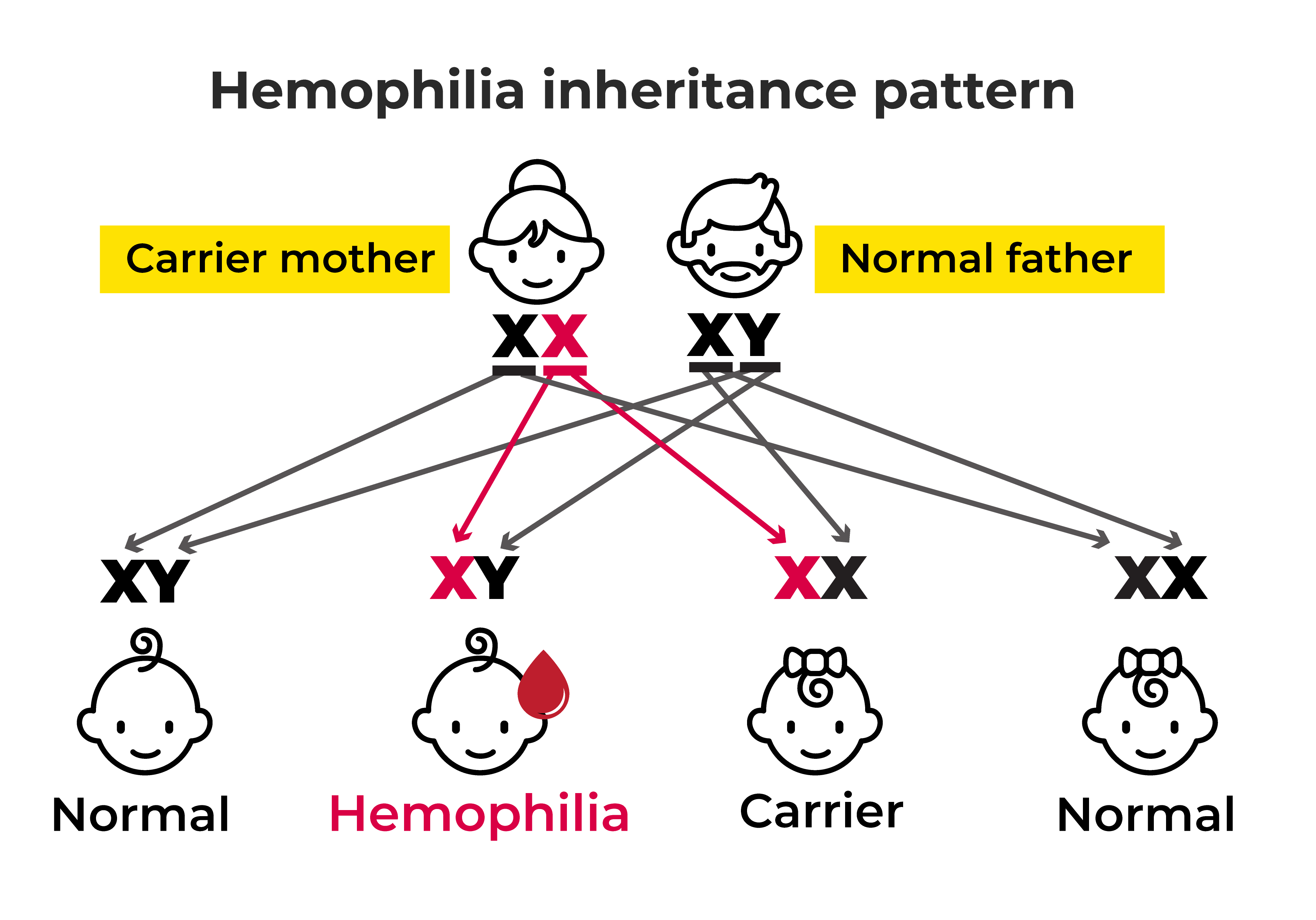

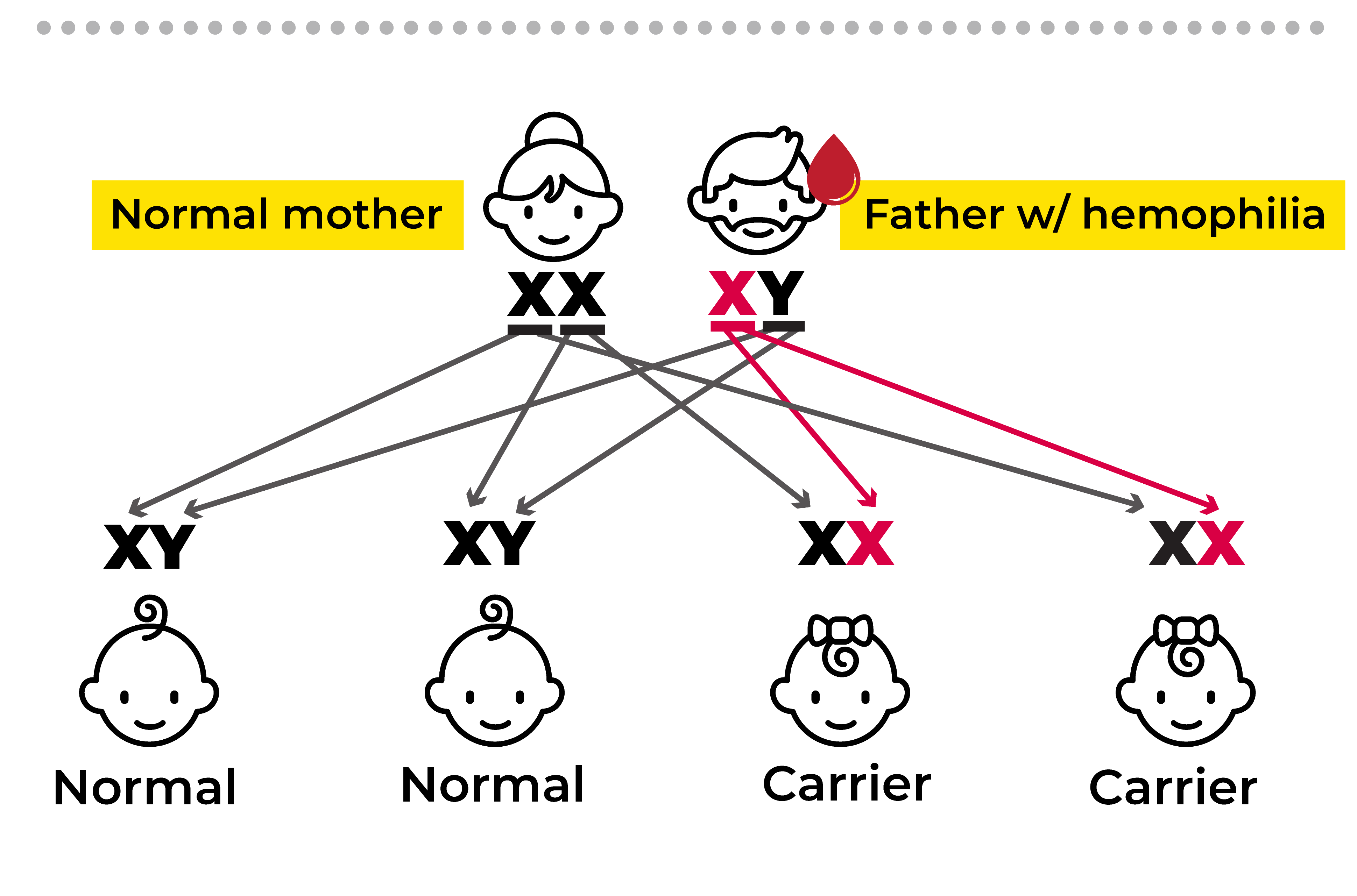

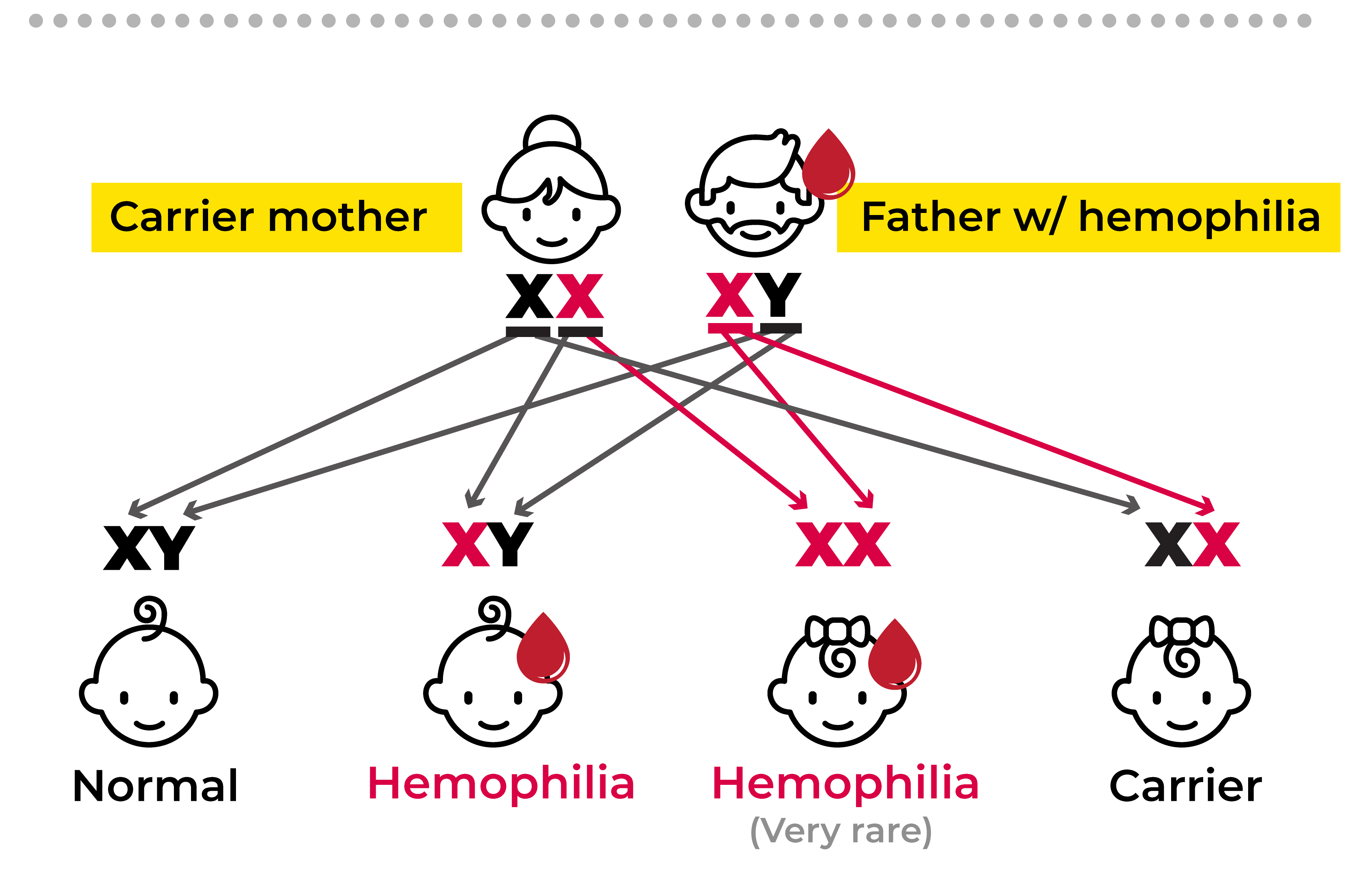

This is due to the fact hemophilia is an x-linked recessive disorder. The inheritance pattern of hemophilia is as follows:

- Males: Males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome. If they inherit an X chromosome with a hemophilia gene mutation, they will have hemophilia because they lack a second X chromosome to compensate for the defective gene. The presence of the hemophilia gene on the single X chromosome in males makes them more likely to develop hemophilia.

- Females: Females have two X chromosomes. If they inherit a hemophilia gene mutation on one of their X chromosomes, they are considered carriers of hemophilia. This means they have a copy of the defective gene but typically do not experience symptoms themselves. However, female carriers can pass the hemophilia gene to their children, both male and female.

If the father who does not have hemophilia and the mother who is a carrier has a child, there is a 50/50 chance of her passing on the affected X chromosome.

- Passing on an unaffected X results in no hemophilia for a child of either sex.

- Passing on the affected X to a female child results in another carrier, as they will receive an unaffected X from their father.

- Passing on an affected X to a male child always results in hemophilia, as this is the only X chromosome they will receive since they must receive a Y from their father. This is the most common way that hemophilia results and is why the condition is more common in men.

- If the daughter were to receive an affected X from both her parents, this would result in full hemophilia in a female. This is very rare; thought to be less than 1% of hemophilia cases.

How is Hemophilia Diagnosed?

Since hemophilia is usually genetic, many families are aware of the possibility of passing the condition on to their children and therefore watch for signs and symptoms in their children or have medical professions screen for the condition after birth. However, some families are not aware of the condition as it can be passed along through carriers and only show up as mild illness.

Hemophilia is typically suspected upon presentation of symptoms. These can include:

- Large bruises following minor injury

- Bleeding for an unusually long time after injury

- Joint pain

- Joint redness and swelling

- Decreased range of motion in joints

- Excessive bleeding with dental procedures

- Blood in your urine

- Excessive bleeding after routine vaccinations

If hemophilia is suspected, the best method of diagnosis is through laboratory blood testing. Hemophilia is most often diagnosed with a blood test to check how much FVIII and/or FIX you have in your blood. The baseline amount is represented as 100%. However, “normal” can be any amount ranging from 50-100%. The severity of the hemophilia depends on the percent of clotting factors in your blood as they range below 100%

- 5-40% (mild hemophilia)

Typically characterized by very few symptoms, and often undetected. Excessive bleeding typically only occurs after serious injury. - 1-5% (moderate hemophilia)

Excessive bleeding is found following minor injuries, though spontaneous bleeding is rare in these patients. - <1% (severe hemophilia)

These individuals have frequent spontaneous bleeds and more severe bleeds following injury.

If you have a normal amount of FVIII and FIX, but decreased amounts of other closing factors, you will likely be diagnosed with another, different, bleeding disorder.

Treatment for Hemophilia

There is no “cure” for hemophilia, but there are effective treatments. In general, the treatment strategy for both hemophilia A and B is to replace the missing factors (FXIII or FIV). This is often done through an infusion (injection) of concentrated FXIII or FIV. There are two types of factor replacement: plasma-based (from human plasma) and recombinant (factors created in a laboratory).

The infusions are often done on a regular basis in order to prevent future bleeds from occurring. However, they can also be given during an acute bleed in order to replenish the clotting factors in your blood when needed.

Other possible treatments for hemophilia depend on the form and severity of hemophilia.

Desmopressin

This medication is a synthetic form of a hormone that is responsible for initiating the clotting process. In milder forms of hemophilia A, it can sometimes be used to stimulate your body to release more FXIII. This can be used for mild injuries or even prophylactically before procedures such as dental work.

Emicizumab

This is a medication that mimics the activity of FXIII in the clotting process. In this way, it is sometimes able to be used instead of factor replacement therapy in some cases of hemophilia A.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 1). What is hemophilia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 1). Women can have hemophilia, too. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, August 8). A new study of hemophilia occurrence finds many more cases in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov

- Hemophilia A. National Hemophilia Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.hemophilia.org

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2021, October 7). Hemophilia. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org

- Current treatments. National Hemophilia Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.hemophilia.org